Artist Ken Lum Captures the Dizziness of Urban Life

We think of cities as places where people come together. The truth is more complicated

To get from the subway to the Ken Lum exhibition at The Image Centre, you must pass through Yonge-Dundas Square, always a destabilizing experience. You’re on a hot, treeless expanse of concrete. People come at you from all directions. You can’t quite tell where the square stops and the street begins. A guy with a megaphone is preaching the End Times Gospel. There are so many digital ads competing for your attention that you feel like you’re walking inside the internet. Nothing coheres. You lose yourself in space and time. A billboard tells you that Janet Jackson is touring Together Again, an album from the ’90s, with Nelly, a rapper from the early 2000s.

Right now, the square is at the centre of a controversy. The city has moved to rename it Sankofa Square—sankofa being a Twi word from the Akan Tribe of Ghana, evoking the importance of historical memory. The change is meant to replace Henry Dundas, the powerful Enlightenment-era Scottish politician who prolonged the abolition of the slave trade. Jennifer Dundas, a retired Crown prosecutor and distant relative of Lord Dundas, is furious. She claims her family’s legacy is being distorted. I have no idea if her case has merit, but after a few minutes in the Yonge-Dundas hellscape, I’m convinced that her anger is misplaced. If the City had really wanted to insult the Dundas Clan, they would have left the name of the square as is.

I’ll say this for Younge-Dundas, though: it makes for a good pre-show to the Lum exhibition, which is all about the strangeness of urban life. Lum, the winner of this year’s Scotiabank Photography Award, is currently based in Philadelphia, although he came up in Vancouver as a leading member of the city’s vaunted photo-conceptualist cohort—artists who work with cameras but traffic mainly in ideas and provocations. I’ve always thought of Lum as an anthropologist with a taste for the absurd. But the former surely implies the latter. To depict humans in the world today is to be a surrealist, almost by definition.

For the series Schnitzel Company (2004 / 2023), a darkly funny work that opens the exhibition, Lum invented a German fast food chain. He then hired actors to pose for twelve portraits, each depicting a Schnitzel Company employee of the month. The images—in which the characters appear in bright yellow work jerseys and tacky Schnitzel Company hats—send up the indignities of late capitalism, which demands not only that people accept lousy work for lousy pay but also that they show gratitude for the arrangement. The guy in the top right corner caught my attention—a dorky dude, improbably named Manfred Klumpp, with a smile that evokes Joaquin Phoenix in Joker. It’s the look of a man who’s about to break. Klumpp was employee-of-the-month in April. One wonders what he did in May and June.

The second room houses the World Portrait series (1991), six white canvasses on which Lum has silkscreened photographs of various urban “types”—women with shopping bags, parents with kids. A city, Lum suggests, is a wildly different entity to its different inhabitants. It is an obstacle course to skateboarders who ollie down its stairways, a smellscape to dogs who sniff the concrete, a realm of possibility to folks who wait on street corners for friends or dates, and a zone of privation to unhoused people who dumpster dive for food. Downtown, we’re physically close. But the experiential gap that separates us is more like a chasm.

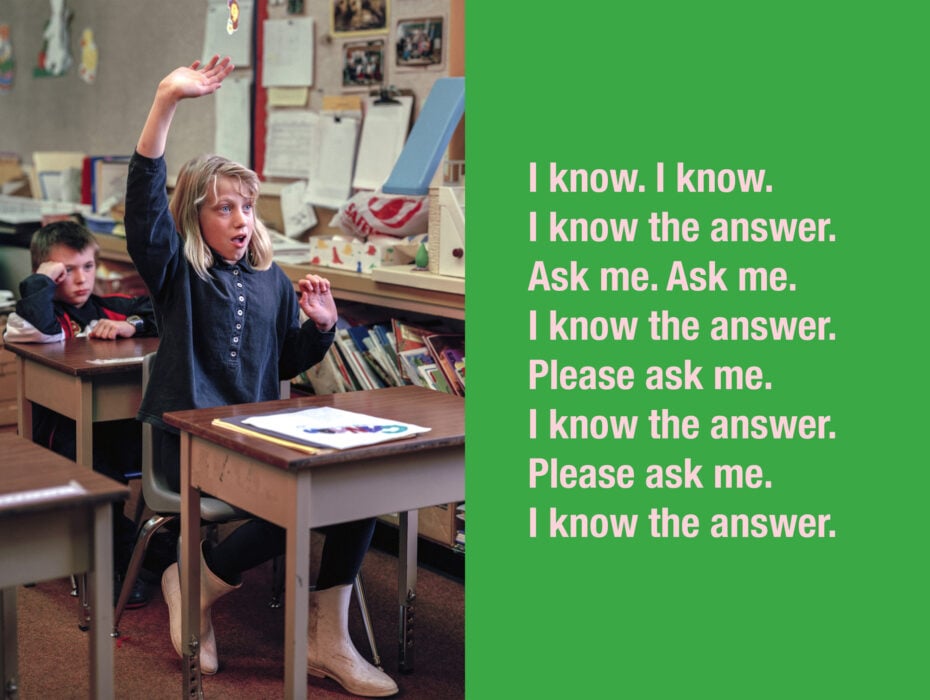

One feels this sense of dislocation most acutely in the third and final room, which houses six panels from the Portrait / Repeated Text series (1994 / 2023)—large-format diptychs with photographs on the left side and chunky wall text on the right. The pieces don’t fit together. You see an image of a standing woman and a man in a wheelchair looking out over a concrete fence (“Please forgive me. I sometimes get frustrated”). Or another of a deshelled, balding man sitting calmly by a roadway (“I’m not stupid. I’m not fucking stupid. You’re stupid.”)

Do words mean anything? Do images? The room—and really, the entire exhibition—feels like a quieter version of Yonge-Dundas. It’s lively, disorienting, and vaguely sinister. Is there a deity who presides over this urban milieu? Maybe it’s Manfred Klumpp, looking down at us with a smile that isn’t a smile at all.