The Secret History of Islamic Architecture

A tour of Islamic architecture in Toronto found in the most unlikely places

When she was an architecture student, Safoura Zahedi learned almost nothing about Islamic design. “There was maybe one PowerPoint slide on the topic,” she says. “The instructor said that, unlike in Christian architecture, Islamic designers didn’t depict icons. They worked with geometry instead.” The images were abstractions, not renderings of the actual world.

The professor’s treatment of the subject was not just cursory but also inaccurate. During the Islamic Golden Age – a period of intellectual ferment between the 8th and 13th centuries – scholars viewed geometry as inseparable from natural sciences. The physical world was a composite tapestry of patterns and shapes. To study points and curves and lines was to study the universe itself.

In late 2022, Zahedi left her job as an architect at the Toronto firm Superkül to visit over 40 cities in 17 countries. She photographed tessellated mosaics in Morocco and India, rosette-capped domes in Malaysia and Türkiye, and elaborate muqarnas (honeycombed vaults) in Egypt and Spain.

I met up with Zahedi this past March, almost a year after her trip had finished, to tour Islamic motifs in Toronto. We started at the Aga Khan Museum, which houses the collection of Shah Karim al-Husayni, spiritual leader of the Nizari Ismaili Muslims. The museum’s logo is an eight-point star, taken from a 10th-century Persian bowl. The star appears everywhere, including on the windows surrounding the central courtyard, which are etched in a pattern resembling a mashrabiya – a vertical screen that filters light and regulates interior temperatures. The building also features abstracted hexagons, most strikingly on the vaults above the auditorium.

The museum is by Fumihiko Maki, one of the most renowned architects in the world. Most Islamic design in the city is of a scrappier vintage. Our tour took us to a St. Lawrence door mural – a play of interlocking stars and polygons – by the artist Bareket, and then to the Masjid Toronto Adelaide, a downtown mosque, where the structural pillars have wooden panels with geometric etchings, some of them cut haphazardly, undermining the symmetry of the patterns. If the Aga Khan Museum offers master craftsmanship, the Masjid Adelaide features the thriftiest kind of vernacular design. It exists not for grandeur but for practicality.

During our final leg of the tour, we went to the most seemingly unlikely place—St. Michael’s Cathedral Basilica, which has rose windows and multi-lobed arches, typologies that can be found in the Khirbat al-Mafjar, an 8th-century desert castle in Palestine. The design of the basilica is unmistakably Catholic, but it’s shot through with Islamic motifs. All gothic buildings are.

How could they not be? When the craftsmen of late-medieval Spain were designing their gilded catedrales—precursors to the neo-gothic churches of Great Britain – they naturally looked to the centuries-old mosques on the southern end of the peninsula. Why wouldn’t they? If you were an architect living a mere horsehide away from the Córdoba mosque—the finest achievement in Islamic design—wouldn’t you too want to check it out? The point here isn’t that Christian architecture is secretly Muslim; it’s that cultures are syncretic. We design here and now by contemplating there and then.

Since arriving back in the city, Zahedi has founded her eponymous studio, which will enable her to bring geometric principles into the built environment. These motifs can give buildings a sense of both intrigue and order, she says. They can connect our built forms back to the natural world—geometry, after all, is nature abstracted—and revive a tradition that has long been with us, even if we haven’t known where to look for it.

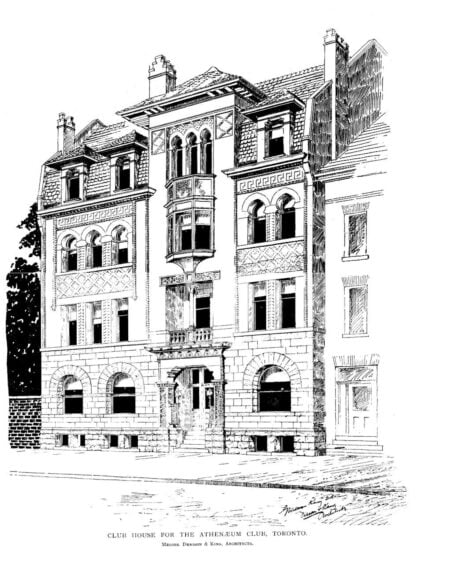

The last stop of our tour was the Athenaeum Club, a one-time labour hall that has since been reduced to a façade – four floors of granite and red brick, in a neo-Moorish style. The Islamic influences are easy to spot: the pinwheel brick patterns evoking Kufic lettering, the bay windows topped with a screen-like latticework, and the pointed arches, which date back to the al-Aqsa Mosque, in the Old City of Jerusalem. The façade is unspectacular. But it contains multitudes—1,500 years of history encoded in brick and bond.