The Well Is a Beautiful Missed Opportunity

At Toronto’s newest megadevelopment, thoughtful architecture competes with lacklustre programming

The Well – a sprawling mixed-use residential complex in downtown Toronto at Front and Spadina – is named after Wellington Street, which flanks the north edge of the property. Copywriters love the name for its association with wellness. “We only live once,” a tagline reads. “Live well.”

Contrary to the marketers, I’m not convinced that “well” has entirely positive connotations. It can be an expression of diffidence or doubt. For instance, you might ask a friend what they think of the new development. And they might respond, “Well…the design is great, but the retail and cultural programming could be better.”

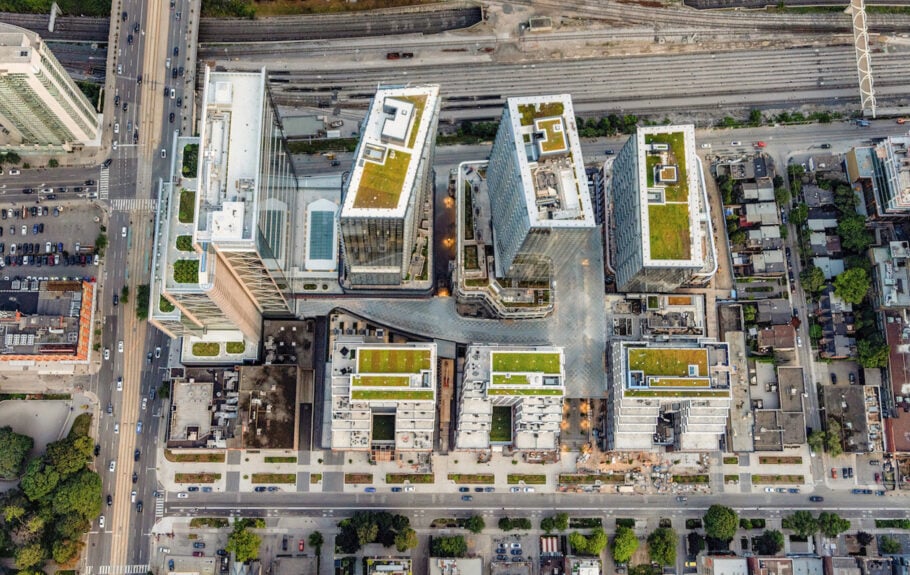

And they’d have a point. The Well occupies a 7.8-acre city block, the place where the Globe and Mail was once edited, typeset, printed, and assembled. In 2012, the Thomson family, who own the newspaper, sold the land to a consortium of real-estate firms. The consortium opted to build seven high rises at the site – one commercial, six residential – with retail offerings at the pedestrian level. It commissioned Hariri Pontarini Architects to draw up a master plan.

To no surprise, HPA delivered. The centrepiece of the project is what partner David Pontarini calls “the spine,” a pedestrian thoroughfare that knits the buildings together and draws people in from the street. “The idea was to make the block super porous,” Pontarini explains. If there’s a single inspiration at work here, it is the classic 19th-century shopping arcade: a sunlit atrium, beneath an assemblage of balconies and walkways. Gorgeous versions of this typology include the County Arcade in Leeds and the Cleveland Arcade. Less gorgeous versions include the Toronto Eaton Centre.

Like the best arcades, The Well Toronto is skylit. It sits beneath a massive glass-and-steel canopy, which undulates like a frozen river, bringing icy lyricism to a neighbourhood of old, rectangular warehouses. But there are equally wonderful, if less conspicuous, flourishes: the footbridges with their exposed beams and wooden soffits, the benches made of reclaimed timber, the grand promenade on Wellington created by setting the buildings back 15 metres from the street. As a parting gift to Toronto, Claude Cormier, the late great landscape architect, has decked out Wellington with polychromatic flagstones and generous planters.

But the main feature of The Well is surely the arcade. The advantage of this typology, Pontarini explains, is that you can cram a lot of retail into a seemingly small area without making the space feel crowded. And lord knows there’s no shortage of retail at the Well. In a single visit, you can stop by Design Republic for mid-century furniture, Le Creuset for enamelled cookware, Gotstyle for bespoke suits, and Bone and Biscuit for homeopathic dog treats. As you go from store to store, you’ll start forming an image in your mind of the people who are likely to buy into the Well – international investors looking to park capital in Canada, perhaps, or financiers seeking a pied-à-terre in the city, or tech bros who think Drake’s For All the Dogs is a good record.

On its website, The Well is billed as a place of “fluidity, creativity, and connectivity.” This may be a suitable description of, say, Yorkville in the ’60s – a dirt-cheap coffeehouse district, where Neil Young jammed with Rick James – but it’s an inapt description of The Well. Synergy happens in free-form spaces, where people (many underemployed) can commune with one another without having to part with much of their money. At The Well, 100 per cent of the homes will be priced at market rate, which, as everybody knows, is punishingly high. Will there be art? Or inexpensive neighbourhood cafes? Right now, there’s Arcadia Earth, an augmented reality exhibition and selfie trap, as well as three new restaurants by the high-middlebrow chain Oliver and Bonacini. The other cultural and dining options are mostly similar: they are places of consumption not creation or discovery.

Oh, well. Things could have been better. Also, they could have been worse. The Well Toronto is a source of housing stock and tax revenue, two things the city desperately needs. The architecture, moreover, is thoughtful and sensitive. But it’s also at odds with the spirit of the endeavour. Cormier and Pontarini have brought a democratic ethos to the project, but the investors who commissioned that project clearly understand it as a market exercise. The website for The Well promises that it will “draw people from near and far” into downtown Toronto. Really, it’ll appeal most to folks who are already there.