The New ROM Renovation Is Not a Repair Job

Okay, but it clearly is

For the first 16 years of my life, the bat cave at the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM)—a reconstruction of an actual cave in Jamaica—was among my favourite places in the city. The cave was decorated with cast stalactites and wax bat models, which hung from the ceiling and threw jagged shadows on the walls. A few other features imbued it with spooky verisimilitude: the drip-drip-drip sound effects, the mirrors arranged to create the illusion of infinite depth, the strobe lights strategically placed to make the shadows flutter. When I visited as a five-year-old, the bat cave scared me. When I visited as a stoned fifteen-year-old, it scared me even more. Then came the renovation.

Today, the bat cave is clean and evenly lit. Instead of the soundtrack and the creepy atmospherics, one hears a recording of a speleologist delivering bat facts, which seem pitched to a grade-five intellect. The project cost $2.75 million, all to transform a cool thing into a boring thing.

But the bat cave retrofit is hardly the worst design “upgrade” the ROM has seen. That, rather, would be the Michael Lee-Chin Crystal, an addition, completed in 2007, by Polish–American starchitect Daniel Libeskind. You might say that Libeskind transformed the museum into a conceptual bat cave: dark, cramped, foreboding—things a public institution should never be.

Libeskind’s idea was to create a sculptural amethyst, an assemblage of diagonal spikes abutting the northwest corner of the original ROM. His symbolism was potent. You could read his metaphor geologically (a new mineral formation on an old rock) or architecturally: Edwardian fustiness colliding with brash postmodernism. He has never wanted for bold ideas.

But in architecture, bold ideas are, on their own, overrated. I could come up with 200 of them by noon tomorrow. I’d have no clue how to turn them into viable buildings, though. Libeskind, it seems, has a similar problem.

The city has never warmed to the crystal. Its defenders—a small, outspoken cohort—attribute our distain to conservatism. In 2017, the architecture citric Christopher Hume told Azure that, “It takes Torontonians years, if not decades, to get over their shock, to learn to accept something, and finally to love it.” In the same article, Alexander Josephson, co-founder of the firm Partisans, strikes a similar note: “Beauty emerges when design misbehaves.”

As comments on aesthetics in general, these takes are spot on—forms that repel you at first can seduce you over time, enriching the way you conceptualize beauty. As comments on Libeskind’s crystal, they miss the point. You can say anything you want about the elusive nature of beauty, but there’s still a meaningful distinction between buildings that work and buildings that don’t.

The crystal may look neat from the outside, but the interior galleries are terrible. The pokey, angular rooms compete for the viewer’s attention with whatever else is on display. Libeskind promised to build a “luminous beacon,” but the crystal wasn’t clad in glass, as that phrase implies, but mostly aluminum panels, with just enough glazing to let in a minimum of natural light. Visitors enter the crystal through a kind of side door, more befitting a passport office than a world-class museum. As for the original ROM entrance—a vaulted lobby with marble stairways and mosaic ceilings? That was closed off. Toronto’s grandest antechamber became its grandest storage locker.

Far from a revitalization, Libeskind’s addition was a cautionary tale—a demonstration of how badly things can go when hubris outruns sensitivity. But in 2016, the museum made a small, refreshingly practical move: it commissioned local firm Hariri Pontarini Architects to retrofit—and then re-open—the original pre-Libeskind entrance. HPA co-founder Siamak Hariri outfitted the exterior space with lights and ramps. The ROM renovation also had the marble stairways refurbished, and the glass mosaic tiles reappointed. “I told the museum leadership,” Hariri says, “that if they’d written me a blank cheque, I could not have created a lobby as excellent as the one they already had.”

The ROM has now rewarded his firm with a more ambitious commission: a renovation to Libeskind’s, um, renovation. The plans, released earlier this year, are backed by $50 million from the Hennick Family Foundation. Hariri refuses to call it a repair job, though. “The point is not that we’re fixing the building,” he says. “It’s that we’re finishing the building.”

You can view this statement as sophistry: the delicate art—parodied by Aristophanes, perfected by Bill Clinton—of talking around the truth. But I see it as diplomacy. Clearly, Hariri understands that you won’t get far in his business if you trash talk your clients.

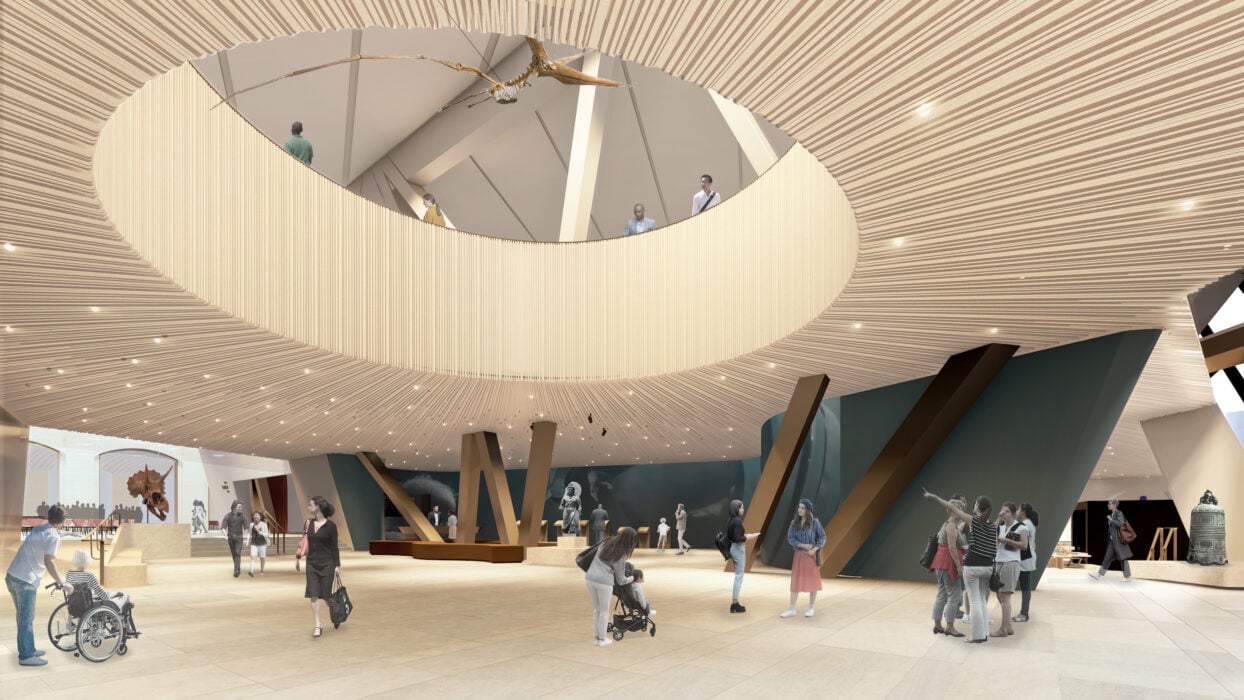

And his design speaks for itself. There will be a brass awning demarcating the crystal-side entrance of the ROM, a reminder that civic buildings should never seem like they’re hiding from the public. There will be wooden slats atop the soffits of Libeskind’s low-hanging foyer, which will give way to a soaring glass canopy, a reminder of the elemental necessity of natural light. Inside this sunlit atrium, and against the brick wall of the original ROM, there will be a sculptural stairway (and rampway) connecting to the various floors and half floors of the old museum. The latest ROM renovation will see a staircase with brass railings and rounded landings resembling lily pads, a reminder that, in architecture, lyricism can coexist with rationality. The new crystal entranceway will be freely open to the public—a collective living room.

All architecture is propositional. To make a building is also to make a statement about the kind of buildings you’d like to see in the world. Hariri isn’t running his mouth about Libeskind. But without words, he’s telling us about the design our city needs—and the design it can do without.