Alex Da Corte Sees What Andy Warhol Missed

In his new exhibition at MOCA Toronto, Alex Da Corte shows that he understands pop culture better than the Pop Art master himself

To figure out the work of 44-year-old Alex Da Corte, perhaps the best pop artist of his generation, you might start by looking at two archival photographs. The first, by Hans Hammerskiöld, captures the late Claes Oldenburg, a ’60s pop-art legend, walking the streets of London and straining under the weight of his own sculpture, a giant tube of toothpaste. The second, by Bill Pierce, depicts Caroll Spinney, the Sesame Street cast member, doing puppetry for Oscar the Grouch while dressed, from the knees down, as Big Bird, the other character he played on the show.

The images were taken before Da Corte’s time, but they capture the Da Corte vibe. They’re cartoonish, surreal and, above all else, devotional. Oldenburg must have loved that ungainly toothpaste tube with paternal fierceness—instead of entrusting it to the care of a gallery attendant, he carried it himself. Spinney was so committed to his alter egos—the overgrown avian and the trash-can dweller—that during busy days on set, he embodied them both at once.

That devotional impulse is present in everything Da Corte does. He’s hardly the first artist to appropriate images from pop culture, but his way is different—more tender, less trollish. Consider his peers: Paul McCarthy, who depicted Snow White doing the kinds of things you’d normally see on the outer fringes of PornHub; Kaws, who transformed the characters in The Simpsons into zombies with X’ed out eyes; and the filmmaker Rhys Frake-Waterfield, who reimagined Winnie-the-Pooh as a sledgehammer-wielding psycho. Nothing is sacred, these artists tell us.

Da Corte seems to believe that everything is. Or rather that, as the journalist John Jeremiah Sullivan wrote, that all people “partake of some holiness.” His first video, Carry That Weight (2003), depicts him struggling to walk down the street with a plush ketchup bottle as tall as he is—an obvious reference to both Oldenburg and the Stations of the Cross. His most famous work, As Long as the Sun Lasts, temporarily installed in 2021 on the roof of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, was a 26-foot-tall imitation of a mobile by Alexander Calder, the mid-century American sculptor. The main character was Big Bird, who perched on one of Calder’s moons and looked out at the New York skyline like an angel at the Annunciation. Da Corte grew up Catholic, in a Venezuelan American family. He’s also gay and loves costumes and camp. All of these facts seem relevant to his work.

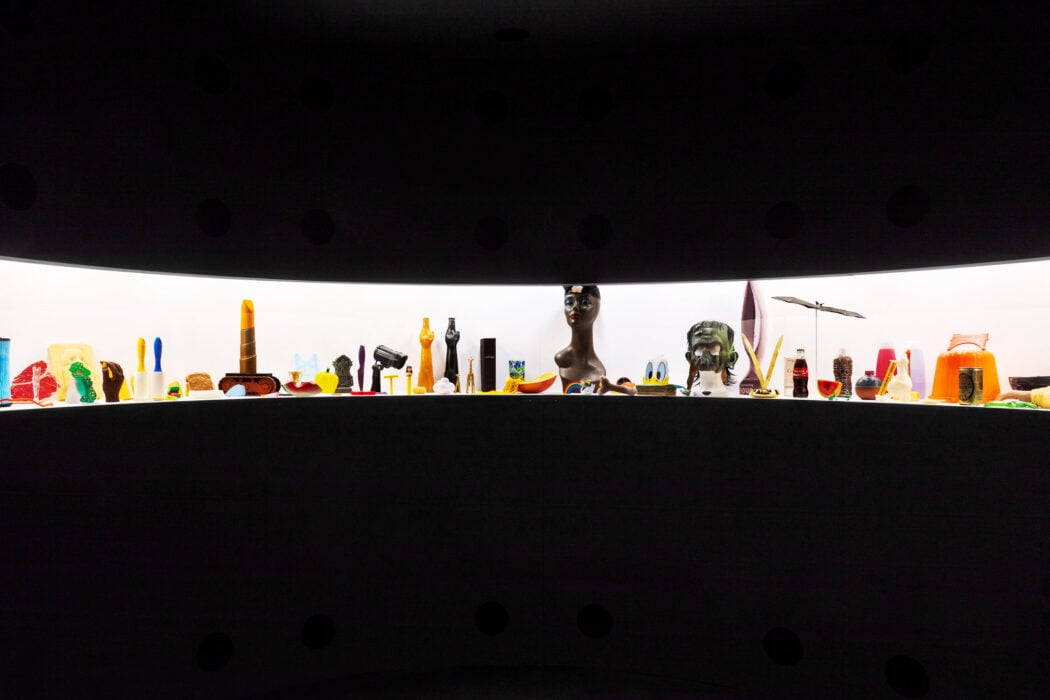

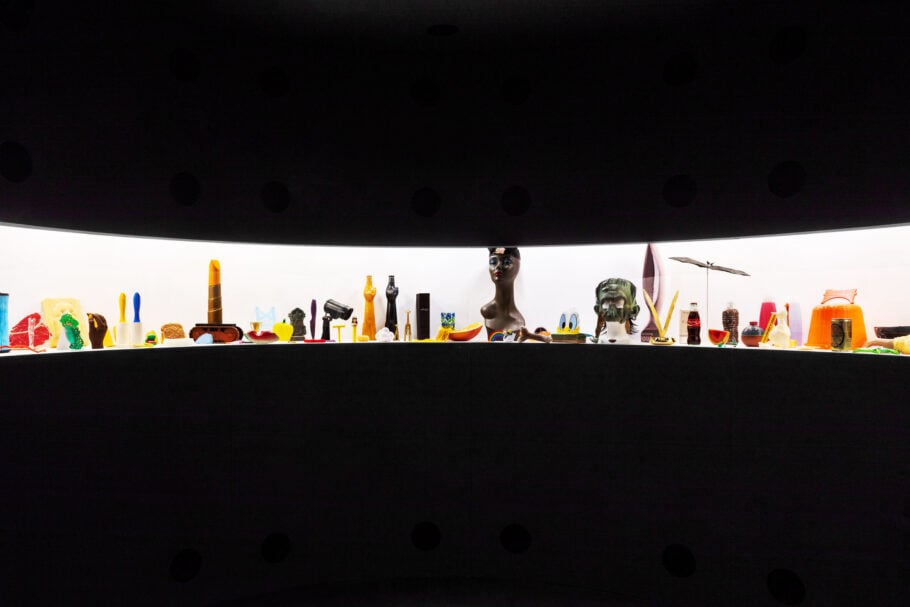

His latest exhibition, Ear Worm, at MOCA Toronto, features a reinstalled version of Rubber Pencil Devil (2018), originally commissioned by the Carnegie Museum of Art, in Pittsburgh. The video is divided into 57 parts, each chapter focuses on a figure from pop culture played by Da Corte. We see Caroll Spinney, in his Big Bird legs, sharing a drink with Oscar. We see Ebenezer Scrooge heading up to bed, except the stairwell is a Stairmaster and he’s doomed, like Sisyphus, to climb forever. We see the Statue of Liberty collapsing under her own weight.

Da Corte chose these characters because they’re ubiquitous. “They are familiar to the point of banality,” he told me. “I find myself wondering, What was the allure from the beginning? Why have they stood the test of time?” All of them, notably, are doing things they haven’t done before. “For me,” Da Corte adds, “the biggest question is, Can these characters change? Can we afford new lives to the things of the past?”

In this respect, he seems locked in a dialogue with his fellow Pennsylvanian Andy Warhol, the man who introduced the world to ironic appropriation. Where Warhol runs cold—his images emit icy glamour—Da Corte runs hot. The MOCA installation is spread over four screens, each bombarding you with music and DayGlo colours. (I interviewed Da Corte in the middle of this scene, an experience every bit as bewildering as you’d expect it to be.) Warhol, ultimately, was interested in sameness. His silkscreens of Marilyn Monroe resemble nothing so much as his other silkscreens of, say, Grace Kelly, Mick Jagger, Wayne Gretzky or Chairman Mao.

He was telling us that pop culture flattens people. To which Alex Da Corte responds: Yes, but then we flesh them out again. And he’s right. We watch prequels and write fan fiction. We hire charismatic hotties, like Colin Farrell, to humanize ugly villains, like Gotham’s Penguin. We speculate that Taylor Swift, a paragon of red state femininity, might secretly be queer, and we reimagine Donald Trump, a man with the attention span of a housefly, as an investigative mastermind routing out a vast global conspiracy. Sometimes, I see my daughter gently chastise her stuffed elephant and for an instant, a figure made of cloth and cotton becomes a living entity.

Like my daughter, Da Corte understands that a being needn’t have flesh and blood in order to live. “I’ve often learned things from the characters I’ve emulated,” he told me. “I’ve discovered that walking in their shoes is different than I thought it would be.” As he spoke, the Wicked Witch of the West sang Blue, by LeAnn Rimes: “So lonesome for you. Why can’t you be lonesome over me?” Oscar the Grouch bopped contentedly behind her.