Jamie Wolfond Unveils Second Limited-Edition Product Drop

The designer adds to his JWS Editions line of experimental releases with a series of cyanotype prints inspired by construction tarps

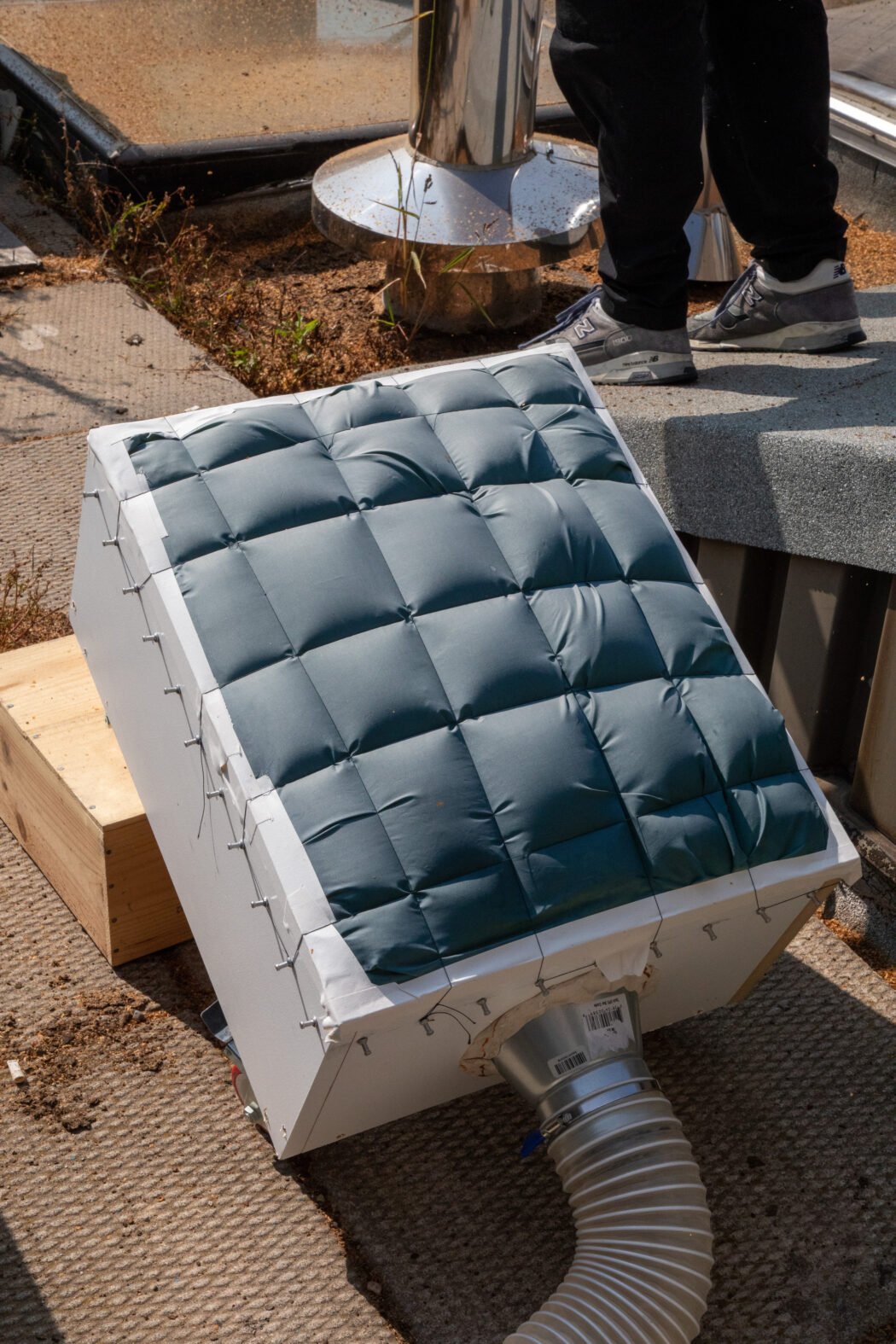

Earlier this month, designer Jamie Wolfond stood on the roof of his studio in Toronto’s Junction neighbourhood, operating a boxy device that looks like a homemade vacuum cleaner but functions more like a giant camera. The contraption is designed to expose cyanotype textiles to light; during each exposure, air is blown inside to inflate the sheet, while a series of strings simultaneously hold it in tension. “We wheel it up to the roof, expose it for three minutes and 15 seconds, then cover it back up with a garbage bag and wheel it down to our bathroom-slash-darkroom,” Wolfond says. It all sounds like the sort of machine that a madcap inventor might pitch to a boardroom of skeptical investors. “We’re very good at coming up with the best way to do something no one else has ever wanted to do,” Wolfond admits with a laugh. But the end results will make you a believer—and maybe even an investor.

Each exposure becomes a beautiful blue slice of frozen time inspired by an overlooked part of Toronto’s urban fabric: the tarps that wrap around construction projects as they’re being built. “There are these beautiful moments that happen when light hits the tarps,” Wolfond says. “In a way, by using a cyanotype to freeze this very uncontrolled moment of architecture, we’re creating a blueprint of this part of the building that was never meant to be blueprinted.” On another level, Wolfond also likes the canvases as showcases of the cyanotype process. “When you put the cyanotype stuff on this textile, it becomes a piece of film. There’s no separation between the subject and the medium—it’s literally film recording the way that this particular film behaves.”

A limited edition of 25 of these unique artworks go on sale today for $250 USD each as the second introduction from Wolfond’s experimental product line, JWS Editions. This latest launch builds upon his first product drop back in June: a moulded pewter trivet (“or a trivet-like piece of artwork, whichever you prefer,” according to the $200 USD product’s web listing). Sold and shipped directly from Wolfond’s studio, these offerings serve as a side hustle to his main business, which involves licensing designs to companies like Muuto, Floyd and Ferm Living.

With JWS Editions, he is free to follow his wildest instincts through to clever, elevated novelties that are on offer for just a short period. “I thought about how we could have a one-night stand with different ideas, basically, where I’m not getting into a long-term relationship just because I want to experiment with something,” he says. Critically, this isn’t his way of trying to leap-frog major manufacturers. “I like the brands that we work with, and I like being that kind of designer,” he says. “This is just an ‘also.’ ” (Sure enough, he has a new light debuting with a well-known brand next month, and recently introduced jewelry with Point Two Five during London Design Festival.)

Of course, when it comes to managing a product line, Wolfond already has some experience. Back in 2014, as a new graduate from the Rhode Island School of Design, he launched Good Thing, a brand that became known for charming homewares like a mirror with a cutout tab that folded into a kickstand. But when he walked away from the company in 2018, the last thing he wanted was to go back to overseeing quality control, inventory and shipping for large product runs. “By the end, I was running something that was respected by a lot of people, but was not really a creative project for me,” he says. And I’m a compulsive designer, so it made no sense.”

After dedicating himself to licensing rather than self-producing his designs, his curiosity-driven approach meant that he quickly started to accumulate a lot of conceptual prototypes. Some of these projects ended up in gallery shows, such as the series of still life vessels that he exhibited at Matter back in 2022. But other explorations produced interesting prototypes that wouldn’t necessarily find success beyond a limited run — making them a tough sell to big manufacturers. Nevertheless, whenever he posted them on Instagram, followers would message about buying them. “People would suggest to me, ‘Why don’t you just make it yourself?’” he says. “And I’d say, ‘Oh, let me tell you why.’ But every time someone said that, I was a little curious — what would I do differently? How would I make it work?”

To prevent JWS Editions from evolving into another Good Thing, Wolfond is committed to handcrafted, limited-run products. “We make a fixed number of something, and when that thing is sold out, it’s over,” he says. Before launching JWS Editions, he also issued a survey via his Instagram to conduct some initial market research. “It was confidence-inspiring to see in the numbers that there are people who want a small thing with a story that makes a big impact,” he says. “I also got a sense of what people were willing to pay for that, and what they wanted it to do.”

The initiative is part of a growing trend of design studios and manufacturers making small-batch collectibles. Castor Design is making its own conceptual experiments and prototypes available through another self-operated line, [SIC], while Swedish manufacturer Hem operates Hem X, a platform for designers to issue artistic exclusives. For his part, Wolfond is encouraged by the possibilities of the limited-edition model. “My thought with JWS Editions is, we can keep throwing darts at the wall for 10 years,” he says. Chances are, his cyanotypes will sell out long before the condos that inspired them finish construction. But through their blue images, a fleeting moment will live on.